The 1960s were, to put it mildly, a transformative period in human history.

A wall sprang up overnight, dividing the city of Berlin in two. The United States and the Soviet Union waged a proxy war in Vietnam that would last twenty years. Man landed on the Moon while mankind nearly landed itself in a full-scale nuclear war as tensions escalated around Cuba. The Civil Rights movement marked a turning point for racial discrimination in the West, and the number of African countries liberated from colonial rule jumped from nine to twenty-six.

In the midst of all this upheaval, one of the most controversial books of the twentieth century was published. Following years of rejection, Rachel Carson compiled her meticulous and irrefutable research into Silent Spring, one of the first and loudest harbingers of the climate crisis.

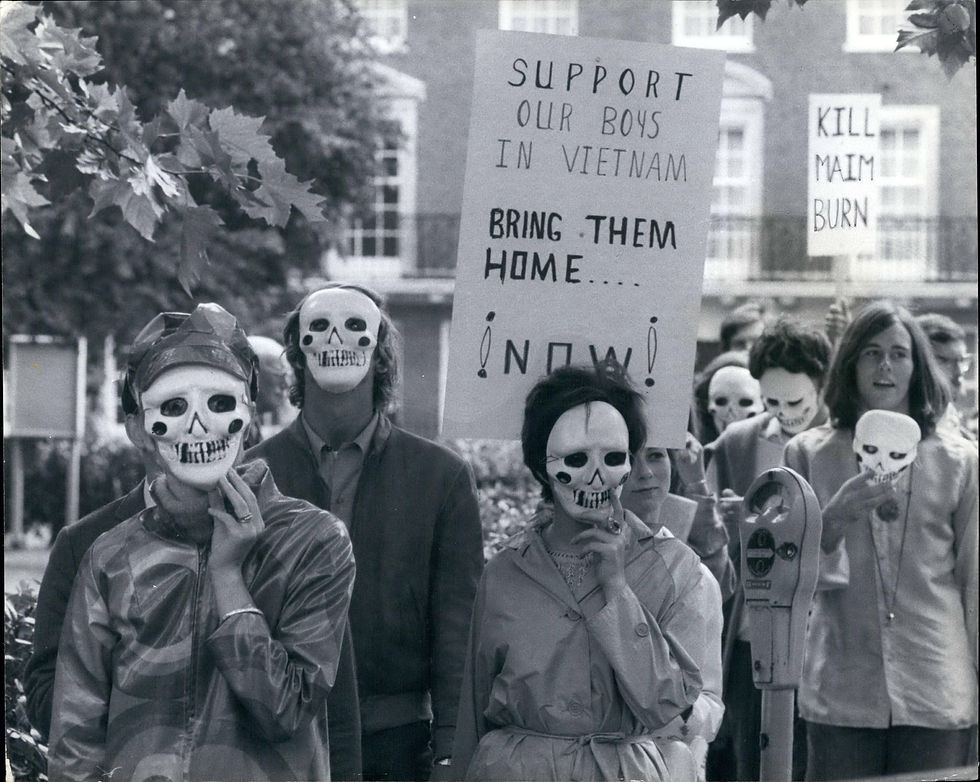

Vietnam Protest At U.S. Embassy in Grosvenor Square, London, 1967

As these literal and metaphorical revolutions played out, a smaller, lesser-known document was also published; one dedicated to preserving locations and buildings borne from, witness to, and sometimes victims of, the workings of socio-political human history.

In 1964, heritage organisations such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM), approved the Venice Charter. A year later, it was adopted by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). While this wasn’t the first document to propose the notion of shared world heritage - it built upon the foundation of the 1931 Athens Charter - given that what are now considered the oldest (manmade) world heritage sites were built over 12,000 years ago, the decision to preserve history feels like an astonishingly recent notion. Nevertheless, on April 18th, ICOMOS celebrates the 60th anniversary of the charter, beginning on the annual International Day for Monuments and Sites, more commonly known as ‘World Heritage Day’.

Crowd Feeding Pigeons in St. Mark's Square, Venice, Italy, 1960s.

In the intervening six decades, the initial rumblings of Silent Spring have become a deafening roar for young people left to manage a planet in decline. Black Lives Matter demonstrates that the fight against racial discrimination is far from over. Ukraine, the Gaza Strip, and Yemen have replaced Vietnam as the latest battlegrounds for conflicts new and old. Only one of the Apollo 11 astronauts is still alive, and walls continue to divide the world despite the fall of Berlin’s barrier in 1989. So, what of that Venice Charter? Viewed through today’s lens of climate change and conflict, is it still fit for purpose?

Angkor Wat, Cambodia

The basic rationale still feels intuitive, proposing as it does that monuments and sites, great or small, be viewed as both works of art and historical evidence. It’s as a result of the Charter that world-renowned sites such as Angkor Wat in Cambodia, India’s Taj Mahal and even entire cities like Venice have been the focus of international conservation efforts. However, this doesn’t mean that the Charter is infallible. With its proposal that any restoration works be clearly distinct from the original construction, criticism to date mostly focuses on whether partly or wholly destroyed monuments should be rebuilt, and, if so, whether modern designs are the most appropriate means of doing so.

The Great Mosque, Djenne, Mali, in the morning. Photograph by Gilles Mairet.

Since the initial Charter was written, changes in this thinking are reflected in projects such as Mali’s mausoleums, which were rebuilt to look as they did before their destruction during the conflict of 2012. Reconstruction of the Old Bridge Area of the Old City of Mostar, which collapsed as the result of shelling of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1993, was also more than mere restitution. At the behest of the Mostar community, the bridge was remade using the same materials and techniques as the original, and now stands, indistinguishable from the old one, as a symbol of reconnection for the people of Mostar.

These examples, which go against the Charter’s principles, imbue heritage sites with a value greater than art or historical evidence. They have since taken on a much more active role in human history, becoming instruments of healing and conservation for surrounding communities.

The Old Bridge, Mostar in 1979. Photograph by Zoran Kurelić Rabko

The Old Bridge, Mostar in 2008. Photograph by Péter Báthory

The process of delivering restorative benefits isn't just achieved through the use of original building materials. Modern technology plays a part too. The University of Bradford’s BReaTHE project shared augmented and virtual reality images of Jordanian Artefacts and Sites chosen by refugee and mixed communities in the Azraq region, increasing project participation by 400 percent. When it comes to leveraging intangible cultural heritage for the benefit of communities, we already know that results are best-felt when communities engage in their own language, and with the relevant values and perspectives taken into account. The same appears to be true of tangible heritage.

As a result of the initiative, researchers documented a number of positive outcomes; the project stimulated discussion between different minority groups, encouraged young people with negative memories of their past to engage with their community’s legacy, and caused a “change in the social structure that has significantly improved the quality of life within the refugee camps”. This is an example of where the values of the Charter, which only consider the literal environs of monuments, can be reimagined holistically for the 21st century.

Tapesty, by CyArk - a nonprofit organisation committed to empowering connections with historic places - offers similar 3D experiences of World Heritage sites.

So, is the charter still fit for purpose? Except for a few overdue tweaks and allowances that would allow for restoration with like-for-like styles and materials, on balance, the answer would appear to be, yes. With many of the same threats looming as when it was first written, however, continuing to place heritage sites, as well as their architects, makers and conservators, at risk, perhaps it’s time to view them differently. A Charter fit for purpose in 2024 would do well to characterise them as more than passive, aesthetic witnesses to our history. It’s time to recognise them as agents of change for the better, and acknowledge that meaningful connection with world heritage doesn’t just protect places and buildings at risk from climate change and conflict, but has the potential to preserve people too.

Interested in reading more articles? Check out all our other pieces, and subscribe to our Substack for a weekly blog!

Comentarios