Whether it’s the peach emoji at the end of a saucy text, or the infamous ‘peach scene’ in the 2017 film, Call Me by Your Name, where the teenage protagonist, Elio (Timothėe Chalamet), uses the fruit as a masturbatory aid, the provocatively-shaped fruit is dripping with suggestive power.

Still Life with Fruit on a Stone Ledge, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, c.1603

In the West, the erotic symbolism of peaches flourished in the Renaissance, pervading the work of artists such as Raphael and Caravaggio. Peaches have also been a long-standing metaphor for sex and sensuality in the literary arts, particularly as a tool for the male gaze.

Detail of the Frescoes in the Loggia of Cupid and Psyche, Villa Farnesina, Rome by Raphael, 1518

The Italian Renaissance poet Francesco Berni, for instance, punned on the Italian, pesca, meaning both ‘peach’ and ‘male bum’.

Oh fruit blessed above all others

Good before, in the middle and after the meal

But perfect behind.

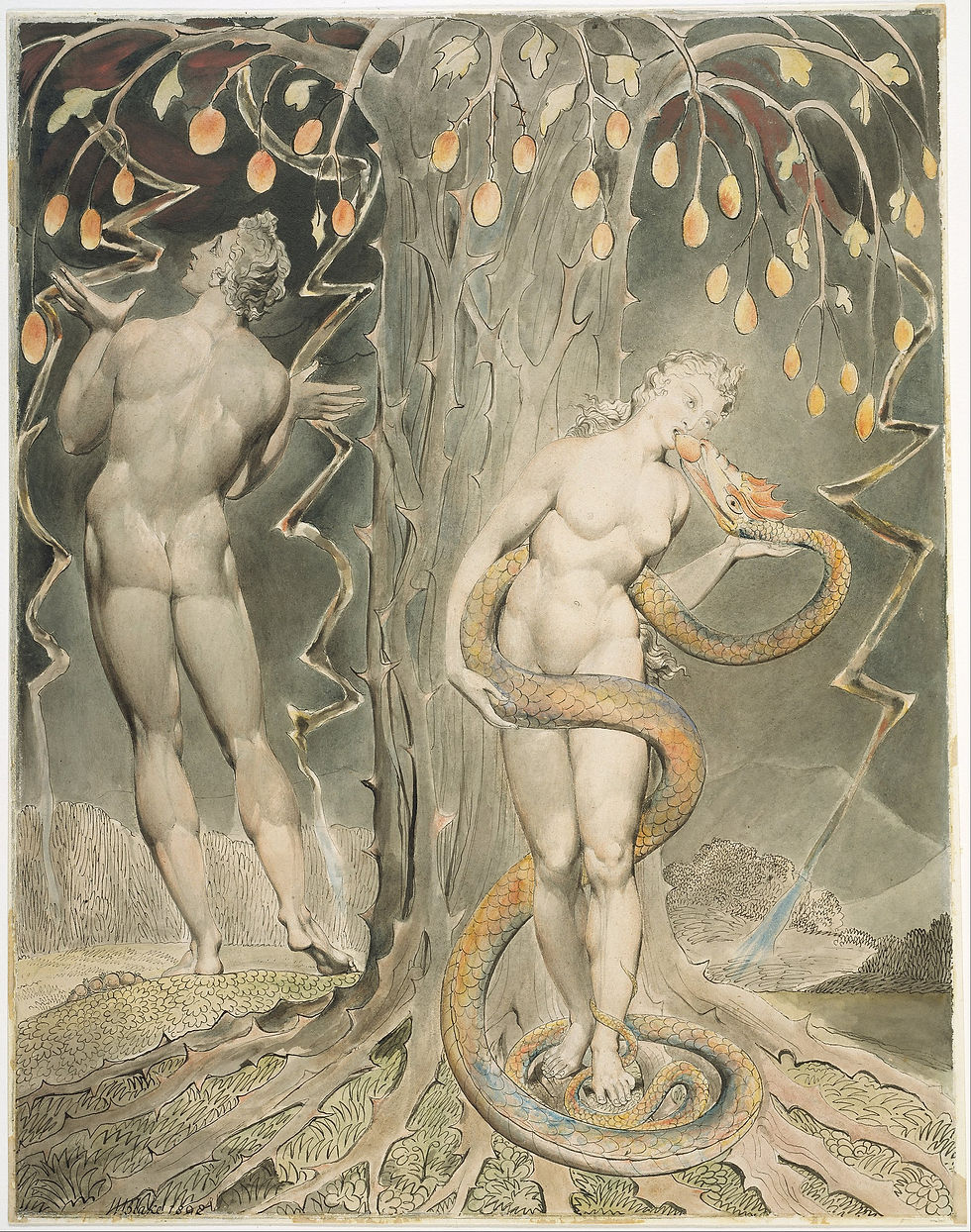

Peaches, however, are not straightforward stand-ins for sex. Or even straight sex, as the Berni poem proves. They suggest transgression. Scholars of Milton have considered that the “downy” apple in Paradise Lost that triggers the Fall in the Garden of Eden is not an apple at all but a ‘persian apple’, or peach.

The conflation may be because both fruits offer fantastic opportunities for trans-linguistic punning that poets just can’t ignore. In French, the word peach (pêche) is awfully similar to the word for sin (péché). In Latin, malum (apple) and malum (evil, sin) are homonyms - different words that look and sound the same. Whatever the language, the evocative form of the peach and its links with forbidden fruit and original sin have contributed to the peach’s literary reputation as the naughtiest fruit in the fruit bowl.

The Temptation and Fall of Eve (Illustration to Milton’s Paradise Lost), William Blake, 1808

T.S. Eliot used peaches to demonstrate impotence in seeking pleasure and failure to socialise with women. “Do I dare to eat a peach?” asks the speaker, in ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,’ reaching for the most impulsive, most imprudent act he can think of when faced with a siren call. To Prufrock, it is an act on par with “disturb[ing] the universe.” He does not.

‘You are eating my peach’, ‘Ice Pick,’ Rached (2020) Dir. Ryan Murphy, written by Ian Brennan

Perhaps it was to rectify Prufrock’s inaction that screenwriter Ian Brennan included an allusion to the poem in an episode of Netflix series Rached (2020); “Excuse me,” says Nurse Rached (Sarah Paulson), addressing Nurse Bucket (Judy Davis), “You’re eating my peach.” The scene turns Eliot’s poem on its head. Prufrock never dares, and so remains on the periphery of life, neither better nor worse off. When Nurse Bucket bites into Rached’s peach, she provokes Rached into action, sparking a revenge plot that will ruin her career. This isn’t the scene’s only poetic reference. An onlooker in the scene interrupts with an observation about the peach in the icebox that recalls William Carlos Williams’ poem, ‘This is just to say’:

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

By substituting plums with peaches, Brennan has created another transgression. What was a poem about a husband seeking forgiveness from his wife for a small, domestic infraction takes on new, sinister and menacing tones. It becomes an argument in a hospital staff canteen, where workplace bullying, systemic homophobia and cruel psychiatric care practices convene to shape one of American literature’s most hated antagonists. All because of a transgression over a peach.

Trailer for Call Me by Your Name, (2017) dir. Luca Guadagnino

If the origin story of the battleaxe Nurse Rached from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (by Ken Kesey) can be, as the Rached narrative suggests, traced to a peach, so can Elio’s coming of age in André Aciman’s novel, Call Me by Your Name. In the novel, the events of the peach scene - and Elio’s inner monologue - expose more transgressions than its film adaptation:

I scanned my mind for images from Ovid — wasn’t there a character who had turned into a peach and, if there wasn’t, couldn’t I make one up on the spot, say, an ill-fated young man and young girl who in their peachy beauty had spurned an envious deity who had turned them into a peach tree, and only now, after three thousand years, were being given what had been so unjustly taken away from them, as they murmured, I’ll die when you’re done, and you mustn’t be done, must never be done?

The scene blurs the boundaries between the real and the imaginary. Though he recounts many transformations as the result of sexual obsession or unsanctioned trysts, such a story does not exist in Ovid’s epic poem Metamorphoses. The scene, however, achieves the same effect as the myths Ovid retold. It blurs the categories of vegetable and animal and of gender, as Elio mixes associations he makes of the peach with male and female anatomy. It blurs the line between consummation and consumption when, later, his lover Oliver eats the peach.

Boy With a Basket of Fruit, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, c.1593

This impossible marriage of contrasts should be too much for just one fruit. Others have vied for the same degree of decadent clout: figs, pomegranates, squashes, melons (we’re looking at you, Harry Styles). But none has captured the artistic imagination as wholly as the peach. Like velvet, touching a peach offers numerous possibilities; soft, downy, yet abrasive and rough, but also harmonious. In its curves and contours, we find our deepest desires and darkest fears. Whether offered up by a talking snake, stolen from the staff fridge, or nestled in the palm of a lover's hand, the peach endures as the emblem of our collective fascination with forbidden fruit.

So the next time you spot one in the fruit and veg aisle at the supermarket, think about what poets and painters have been trying to tell us about peaches, even after all this time. Do you dare?

Interested in reading more articles? Check out all our other pieces, and subscribe to our Substack for a weekly blog!

コメント